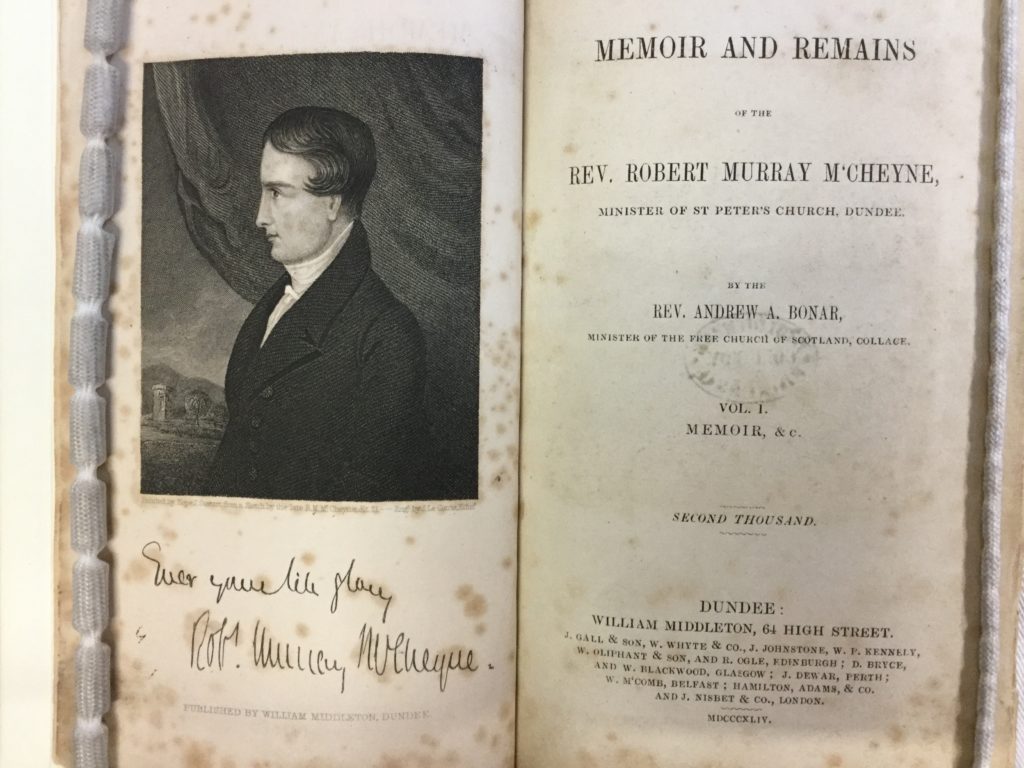

Andrew Bonar’s Memoir and Remains of Robert Murray M’Cheyne is a bonafide spiritual classic.

Consider the following commendations and comments from some of God’s great men:

- “This is one of the best and most profitable volumes ever published. The memoir of such a man ought surely to be in the hands of every Christian and certainly every preacher of the Gospel.” — C. H. Spurgeon

- “That wonderful classic.” — W. Robertson Nicoll

- “I am constantly hearing of the great good that book has been the means of doing.” — Alexander Whyte

- “That converting and sanctifying biography.” — Bishop Handley Moule

- Robert Murray M’Cheyne’s biography written by his friend Andrew Bonar is one of my most treasured possessions and has been a companion throughout almost all of my Christian life. M’Cheyne died when he was twenty-nine, but his life story has been for me personally a model of grace, and his ministry pattern a model for service. It is a book every young Christian man should read—more than once.” — Sinclair B. Ferguson

For my own experience, nothing outside of Scripture has done me so much spiritual good as Bonar’s Memoir.

Something of a Backstory

After M’Cheyne’s death in 1843, his close friends were eager to commission a story of his life and ministry. Because he was M’Cheyne’s closest friend and possessed the required gifts to tell the tale, Bonar was chosen to write the memoir. The Great Disruption of 1843 distracted him for a time—from May through September of that year. When Bonar finally put pen to paper, he wrote with determination, finishing the manuscript only three months later. The result was a volume of 648 pages, 166 of which are Bonar’s original biography. The remainder of the work contains M’Cheyne’s letters, sermon, and miscellaneous treatises.

Once it released, the book sailed off the shelves. The Jewish Herald said the Memoir “commanded a sale almost unprecedented in the annals of religious biography.” Andrew Palmer, who wrote a doctoral thesis on Bonar, says, “Though Bonar could have made a great deal of money from the publication of the Memoir, he received only a very moderate sum, and the copyright was originally secured by the remaining members of M’Cheyne’s family.”

One Author’s Experience

One of the more fascinating observations in my studies on M’Cheyne was Andrew Bonar’s experience in writing the Memoir. Here’s what we find in Bonar’s Diary and Letters about his work on the Memoir and its subsequent reception:

One of the more fascinating observations in my studies on M’Cheyne was Andrew Bonar’s experience in writing the Memoir. Here’s what we find in Bonar’s Diary and Letters about his work on the Memoir and its subsequent reception:

- April 1843: “I am urged to have my Memoir of Robert M’Cheyne ready by the end of the year.”

- September 30, 1843: “Beginning to write Robert M’Cheyne’s Memoir. This fills up all my leisure time.”

- December 23, 1843: “Finished my Memoir of Robert M’Cheyne yesterday morning. Praise, praise to the Lord. I have been praying, “Guide me with Thine eye’ I may soon be gone”; but I am glad that the Lord has permitted me to finish this record of His beloved servant. Yet it humbles me. My heart often sinks in me. Just to-night I saw my soul full of nothing but self, and all that comes forth seems a black stream of selfishness.”

- March 4, 1843: “The Memoir of Robert M’Cheyne is now just about to appear. O that it may be blessed!”

- March 23, 1843: “It was on this day of the week last year, about sunset, that a messenger came and told me of Robert M’Cheyne’s illness. It makes the day very solemn. I have grown little indeed by that providence, though it seemed sent to us for that intention. Several of us are to observe Monday as a season of special prayer and fasting to ask a blessing on the Memoir and the raising up of many holy men.”

- January 4, 1845: “Looking back on last year I feel how awfully little has been done for God. My soul has grown very little. My ministry this year has been little blessed. The Memoir of Robert M’Cheyne and my Tract on Baptism seem to me the chief way in which the Lord has been using me this year to any extent.”

- March 27, 1845: “Received a letter to-day telling me of the blessed effects of Robert M’Cheyne’s Memoir on one in London, in which he refers to the anniversary of his death—the 25th, a day I did not forget. Many tokens have I received of the Lord’s blessing that book. It roused me to thanksgiving, and I began to think that, if I oftener thanked God at the moment, I might oftener hear of His blessing upon my labours. He lets us know in order that we may give praise.”

- December 18, 1846: “I see that the prayers of so many friends who pray for me are, no doubt, the cause of my getting peculiar help in writing the Memoir and then, the [Commentary on] Leviticus, I have often felt things in study so plainly given me, not at all like the products of my own skill, that this is the way in which I account for them. The Lord sends them because of people praying for me.”

- May 1, 1853: “After my Communion I heard of blessing upon the Memoir of Robert M’Cheyne in the case of one in Edinburgh.”

- December 31, 1856: “Encouraged by hearing of a soul awakened through reading Mr. M’Cheyne’s Memoir in

Guernsey.” - November 17, 1860: “Got to-night from Holland a Dutch translation of M’Cheyne’s Memoir. Praise the Lord, O my soul, that thus good is done in foreign lands by that book.”

- December 31, 1864: “It is now evening, and just at the close of the most memorable year since the death of Robert M’Cheyne (Bonar’s wife died on October 15th). I shall remember this year, in the ages to come, as the year I came in a special sense into the valley of Baca. My heart still fails me as often as I realize my loss. But, Lord, make my beloved wife’s removal as blessed to me as was the death of Robert M’Cheyne to the public through means of his Memoir.”

- July 13, 1876: “A minister from America cheered me greatly by telling me how M’Cheyne’s Memoir has been used there.”

- August 2, 1884: “Have heard lately oi two cases in which the Memoir of Robert M’Cheyne has been blessed: one here, another in England.”

- July 21, 1891: “Heard to-day that Mr. Sinclair, minister of Kenmore, who translated the Memoir of M’Cheyne into Gaelic, received more than one letter telling that it had been blessed to the reader.”

Lessons Learned

It’s striking to see the place the Memoir occupied in Bonar’s life. For nearly a half-century, words of the book and thoughts about the book were close to his mind.

In reading through Bonar’s notes, two simple spiritual lessons came to my mind. First, how often God works through biography. You don’t have to be an expert in church history to know how a religious portrait launched many mighty men and women into Christ’s service. The nineteenth century was an era in which biographies flourished. Our age has so shunned history that many have lost the desire to learn not just from, but also about the old saints. If the trend continues, it will mean poverty in our piety. We need another generations of pastors and scholars whom the Spirit fuels and fills to right Christ-exalting biography.

Second, the great books fly on the wings of prayer. Bonar comments about how a day of fasting and prayer was set aside before the Memoir went out for sale. Prayer for the book didn’t stop; it continued throughout the years. What we need today are books that have prayerful authors and prayerful readers. Let us pray down God’s blessing on the great books. Let us yearn for God to glorify His name and His Son through the expansion of edifying works throughout the world.

Here’s how Crossway describes the book:

Here’s how Crossway describes the book:

After hearing the great Dr. Fairbairn preach, Jowett told his students at Airedale College, “Gentlemen, I will tell you what I have observed this morning: behind that sermon there was a man.” Although The Preacher provides scant autobiographical information, I always have same sense in reading Jowett’s work—there is gravity in his message.

After hearing the great Dr. Fairbairn preach, Jowett told his students at Airedale College, “Gentlemen, I will tell you what I have observed this morning: behind that sermon there was a man.” Although The Preacher provides scant autobiographical information, I always have same sense in reading Jowett’s work—there is gravity in his message.