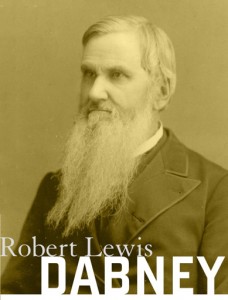

A forgotten contribution to the modern conversation on preaching is Robert Lewis Dabney’s Evangelical Eloquence: A Course of Lectures on Preaching.

A forgotten contribution to the modern conversation on preaching is Robert Lewis Dabney’s Evangelical Eloquence: A Course of Lectures on Preaching.

The legendary Southern Presbyterian minister originally published the work as Sacred Rhetoric (a quite lovely title) in 1870 as the fruit his seventeen years at Union Theological Seminary. Contemporary preachers would be well served by the whole book, but lectures 7-8 are particularly helpful. These two lectures offer the following seven “cardinal requisites of the sermon”:

- Textual Fidelity. This means “sticking to one’s text.” The preacher’s very nature as a herald demands such fidelity, for the first quality of a good herald is the faithful delivery of the very mind of his king. God’s thoughts, not ours, are to occupy a primary place in the sermon.

- Unity. The sermon, like every work of art, needs unity. Dabney says rhetorical unity requires two things: 1) a main subject for the discourse, and 2) a main impression for the hearer. Singleness in exposition and application are unity’s best friends.

- Evangelical Tone. The proclamation of the gospel requires a gracious character; it is the place “where mercy and truth meet each other, and righteousness and peace kiss each other.” This requirement assumes that the sermon will be predominately evangelical. Or in contemporary jargon, “gospel-centered.”

- Instructive. This does not mean a sermon should be accused of “odious intellectualism.” An instructive sermon instead means food for feeding. The instructive sermon will have an important point, rich in substance, faithfully delivered to the congregation’s life.

- Movement. Movement, said Vinet, is the royal virtue of style. Dabney says movement is what will make a discourse eloquent. What’s movement? “It is, in short, that force thrown from the soul of the preaching into his sermon, by which the soul of the hearer is urged, with a constant and accelerated progress, toward that practical impression which is designed for the result.” Preaching needs passion.

- Pointedness. There must be a main point to the sermon, clearly understood by the hearer, intended to excite the soul. From there the preacher must have a clear idea of where his is going and his congregation must understand, once he gets to the end, how and why he got there.

- Order. The sermon needs to be properly ordered and divided along expositional lines. “Each thing should be said in its right place.” Dabney has little time for the wandering discourse and aimless exposition, for “disarray is displeasing.” If a church member is able to recall the sermon’s contents a few day’s after the preaching event, the sermon likely had order. If the church member can’t remember anything from the sermon other than the preacher did a good job, the sermon like had no order. Order brings benefit to the hearer.

Once you get used to the late-19th century prose, I predict you’ll be amazed at how profitable this book is.