Just as Catholicism influenced the spirituality of mainline Protestants in the 20th century, so too did mainline Protestants influence evangelical spirituality. The influences are many, but this essay will focus on the spiritual formation movement, increasing openness to the miraculous gifts, egalitarianism, and homosexuality.

The Spiritual Formation Movement

For most of the 20th century evangelicals had never heard of the phrase “spiritual formation.” Yet, by the turn of the century “spiritual formation” was a buzzword in evangelical denominations and networks. Many seminaries today not only offer spiritual formation classes, but even have departments of spiritual formation. What is it? Spiritual formation speaks of the shaping process by which a person’s spirituality is shaped, and is thus uniquely concerned with the dynamic means by which one grows in Christlikeness. Its main proponents are luminaries such as Dallas Willard, Richard Foster, and Eugene Peterson.

Mainline versions of spiritual formation often meant experimenting with a diverse array of practices. In the late 1900s mainline retreats for spiritual formation would adapt themes from medieval mystics and have workshops on the Labyrinth or Enneagram. Some spiritual formation proponents even encouraged Buddhist techniques to help spiritual growth. In a Christianity Today article from 2002 entitled, “Three Temptations of Spiritual Formation,” Evan Howard writes, “One popular retreat and spiritual [formation] training center in my region offers common meals, massage, inner healing, evening prayer, in-depth dream work, daily Eucharist, and “mandala explorations.” Mandalas (artistic, usually circular, designs) appear in a few religious traditions—in Native American designs, in Gothic rose windows, and especially in Tibetan practices.” It seemed as though much of the spiritual formation in the mainline was indeed “spiritual,” but hardly “Christian.”

Much of the evangelical adaptation of spiritual formation picks up on time-tested, ordinary means for growth in Christlikeness. Foster, in his Celebration of Discipline, provides a chapter each on the following disciplines: mediation, [contemplative] prayer, fasting, study, simplicity, solitude, submission, service, confession, worship, guidance, and celebration. The mainline influence is particularly seen is in how some evangelicals stress greatly intuitive and individualistic notions of spirituality. Yet, whereas the mainline feels no great need to tether this intuitiveness to Scripture, many evangelical teachers of spiritual formation seek to submit the intuitive pursuits to Scripture and not neglect the reality of sin and the need for a Savior. Spiritual formation is thus not something done to simply promote spirituality, but something done to pursue godliness, as revealed in God’s Word.

The Third Wave

Quite possibly the greatest effect mainline Protestant spirituality brought to evangelicalism is “The Third Wave” movement. It was at the beginning of the 20th century that Pentecostalism began and quickly found a place in American—if not evangelical—life. Charles Parham taught that the baptism of the Spirit was subsequent to conversion and was evidenced by speaking in tongues. His young disciple William Seymour would eventually take the Pentecostal doctrine to Los Angeles where, in 1906, a revival broke out. This revival lasted for roughly nine years and led to the rapid growth of the Pentecostalism in America. Yet, for most of the first half of the twentieth century Pentecostalism found little respect among mainline denominations and thus had little effect on Protestantism as a whole. This began to change when Dennis Bennett—an Episcopalian priest in Van Nuys, California—claimed to have been given the gift of tongues. This event was a watershed moment for Pentecostalism. It eventually led to many Catholics and mainline Protestants to become “Charismatic” in their orientation. While Pentecostals teach a subsequent Spirit baptism leading to the gift of tongues, Charismatics accept a “baptism in the spirit” by faith without accompanying manifestations while later seeking to “yield to tongues,” not as “initial evidence” but as one of the authenticating gifts of the Spirit. Throughout much of the 1960s and 1970s, a Charismatic renewal swept through the mainline denominations and moved the continuation of all spiritual gifts to the forefront of much evangelical thought.

The great adaptation of mainline Charismatic renewal practices began to broadly happen in the 1980s. Peter Wagner, of Fuller Theological Seminary, coined the term Third Wave, saying, “The first wave was the Pentecostal movement, the second wave was the Charismatic movement, and now the third wave is joining them.” Third Wave adherents thus made it clear that while they were the natural succession to Pentecostal and Charismatic practice, they were distinct. What made the Third Wave proponents different from Pentecostals and Charismatics was they did not teach a subsequent baptism of the Spirit to conversion, but they did believe in the continuation of all miraculous gifts. A believer was baptized in the Spirit upon conversion and all gifts were to be pursued, but not all gifts would be received.

Third Wave belief and practice was typified by the Vineyard Movement, which went through astonishing growth under John Wimber in the mid-1980s–late-1990s. The movement was characterized by signs and wonders and swept up many notable evangelicals including Dallas Theological Seminary professor Jack Deere, as well as theologian Wayne Grudem, and Sam Storms. Another prominent evangelical Third Wave movement is Sovereign Grace Ministries.

Perhaps the greatest example of evangelicalism’s fascination with and adaptation of The Third Wave is John Piper. One can read Piper articles and sermons circa 1990 to see a pastor intrigued with John Wimber, while simultaneously being unsure of his teaching. At Lausane II in Manila Piper spent much time learning from Jack Hayford and John Wimber. In 1990 Piper took fifty-eight leaders and members from his church to investigate Wimber’s ministry further at The Vineyard’s “Holiness Unto the Lord” conference. Piper came back to Bethlehem Baptist Church with a series of “Kudos & Cautions” for Vineyard and Wimber. As one pays attention to Piper’s ministry, his public fascination with The Third Wave has diminished even if his Third Wave sympathies remain.

Piper appears emblematic of a large swath of evangelicals in our time, Christians who are open to all miraculous gifts, yet don’t pursue or practice all gifts with zeal. In many ways, it seems as though the rising evangelicals today are something of a “Fourth Wave,” which can be quantified in the statement, “Open to all spiritual gifts, but cautious in the use of all spiritual gifts.”

Egalitarianism & Homosexuality

Towards the end of the 20th century many mainline Protestant denominations reflected the larger culture’s changing attitudes towards the role of women and homosexuality. It became increasingly common for mainline denominations to ordain women to pastoral ministry and in time many would ordain a homosexual to gospel ministry. In the late 1980s evangelicals reacted to this growing change with the publication of The Danver’s Statement in 1989. From this public statement of complementarianism The Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood began to lead the charge for a “regrounding” of evangelicalism on the Bible’s teaching on gender roles and sexuality.

The evangelical seminaries bear testimony to the war that raged during this time over egalitarianism and complementarianism. Many evangelical seminaries (Fuller Theological Seminary being among the most prominent) had faculty members that were either openly confessing egalitarianism or either on the way to egalitarianism. Southern Baptist Theological Seminary is probably the most visible seminary to go through an internal—yet, still quite public—battle over the matter and come out on the complementarian side.

It must be noted that many egalitarians would consider themselves evangelicals. They believe, from Scripture, that women can be ordained to the ministry but still hold to the inerrancy of Scripture and the urgent need for preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ. Other evangelicals believe complementarianism to be “a gospel issue,” and thus egalitarianism is incompatible with a pure gospel.

In mainline Protestantism we saw many denominations confessing egalitarianism soon confess openness towards homosexual practice and in our time this is the greatest place of mainline influence on evangelicalism. Just as the matter of homosexuality seems to be the current dividing line in our broader culture, it seems to be the next dividing line of spirituality among moderates and conservatives alike.

Historical Appreciation

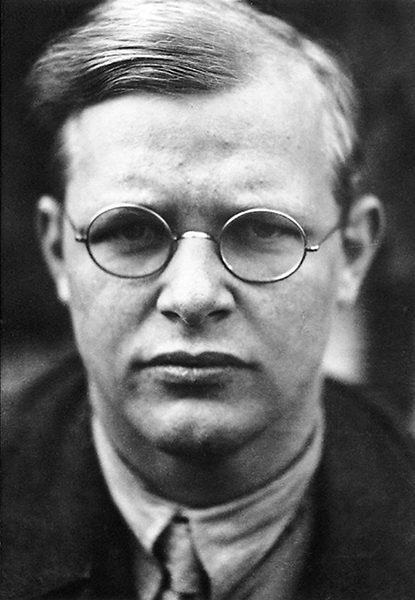

A final evidence of the mainline’s influence on evangelical spirituality can be seen in the unabashed appreciation of mainline figures like Deitrich Bonhoeffer and C.S. Lewis. In 2010 Eric Metaxas published Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy. Metaxas’ book was something of a sweeping and sensational publication in our country, shooting up the bestseller lists and even paving the way for Metaxas to speak before President Obama at the National Prayer Breakfast. It’s success was a great indication of how many evangelical Christians are influenced by a mainline Protestant from Germany.

C.S. Lewis also continues to occupy a large plage in evangelical life. In 2013 Desiring God devoted their national conference to the theme “The Romantic Rationalist: God, Life, and Imagination in the Work of C.S. Lewis.” In addition to his Chronicles of Narnia, Lewis’ books The Screwtape Letters, Mere Christianity, and The Problem of Pain have exerted a large influence on the life and faith of evangelicals.

Greeks Bearing Gifts

Greeks Bearing Gifts