My first exposure to Dietrich Bonhoeffer came when, as a twenty-two year old student pastor, I picked up a copy of The Cost of Discipleship on sale for $3 at a local Christian bookstore. I found Bonheoffer’s prophetic-like earnestness utterly transfixing and his fervor for following Christ totally convincing. Discipleship was something like spiritual accelerant on the fire of holy-love for Christ. Eventually the book found a cherished place in my study, but a somewhat forgotten place in my life. That was until 2010 and the arrival of Eric Metaxas’ Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy.

My first exposure to Dietrich Bonhoeffer came when, as a twenty-two year old student pastor, I picked up a copy of The Cost of Discipleship on sale for $3 at a local Christian bookstore. I found Bonheoffer’s prophetic-like earnestness utterly transfixing and his fervor for following Christ totally convincing. Discipleship was something like spiritual accelerant on the fire of holy-love for Christ. Eventually the book found a cherished place in my study, but a somewhat forgotten place in my life. That was until 2010 and the arrival of Eric Metaxas’ Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy.

A Counterfeit Hijacking?

Metaxas’ book was something of a sweeping and sensational publication in our country, shooting up the bestseller lists and even paving the way for Metaxas to speak before President Obama—and quite humorously so—at the National Prayer Breakfast. Believe it or not, up until this point I knew next to nothing about Bonhoeffer’s labor against the Nazis and as an armchair historian of World War II I quickly became absorbed in Bonhoeffer’s covert affairs. I greatly enjoyed the book and so upon completion I proceeded to see if scholars and reviewers enjoyed it as much as I did. Suffice it to say, I was rather stunned to see articles like “Metaxas’ Counterfeit Bonhoeffer”[1] and “Hijacking Bonhoeffer”[2] denouncing the book as “a Bonhoeffer suited to the evangelical taste.” Victoria Barnett, the editor of the English edition of Bonhoeffer’s Works, called Metaxas’s portrayal of Bonhoeffer’s theology “a terrible simplification and at times misrepresentation.”

A Theological Enigma

This was altogether alarming. My scratching of the Bonhoeffer surface and correlative conversations had led me to believe Bonhoeffer was just another chip of the Evangelical Block. So, with the assistance of a theological mentor, I began to dabble in Bonhoeffer’s doctrinal convictions and what I found was something of a theological enigma; a teacher who could garner evangelical praise in one breath and scorn in the next.

For example in his 1932-1933 lectures eventually published as Creation and Fall Bonhoeffer says, “The Bible is nothing but the book upon which the Church stands or falls.”[3] That’s a thoroughly evangelical statement. Yet, in the same book, when commenting on Genesis 1:6-10 Bonhoeffer writes, “Here we have before us the ancient world picture in all its scientific naivete.”[4] And, just a paragraph later, the German giant says, “The idea of verbal inspiration will not do.”[5]

All this from the man who would in the next 5-6 years would offer Discipleship and Life Together as enduring gifts to the church; works that have perpetuated profound Christ-centered and Bible-saturated spirituality.

To understand why Bonhoeffer has no small fans among both liberals and conservatives, we need to get our minds around the historical and theological context of Bonhoeffer’s thought.

A Child of German Liberalism

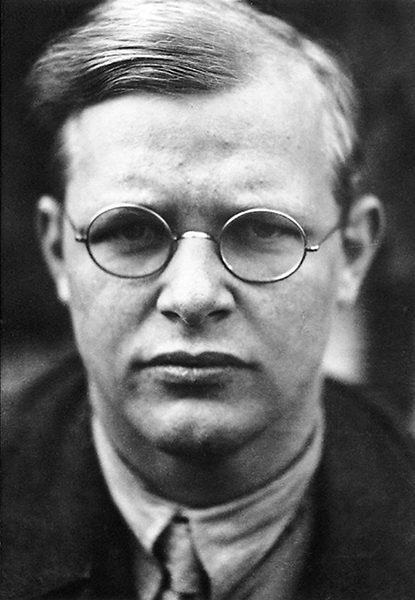

Bonhoeffer was born on February 4, 1906 “into a family of prodigiously talented humanists.”[6] His father Karl was a doctor who had little interest in religion, while his mother Paula dutifully took Dietrich and his six siblings to Lutheran services. It was clear from an early age that Dietrich possessed great intellectual (as well as musical and physical) talents. Not long after his older brother died on a World War I battlefield thirteen-year-old Dietrich announced that he would become a theologian. Bonhoeffer’s older brother were flummoxed with this plan, saying to the budding professor, “Look at the church. A more paltry institution one can hardly imagine.” To which Dietrich responded, “In that case, I shall reform it!”

In 1924 Bonhoeffer began his theological studies at Friedrich-Wilhelms University in Berlin. Founded in 1809 by the Friedrich Schleiermacher—“The Father of Christian Liberalism”—the university boasted an unrivaled faculty of Adolph von Harnack, Karl Holl, and Reinhold Seeburg. It is important to note that it was here at university Bonhoeffer immersed himself in the philosophical and theological convictions of Kant, Hegel, Kierkegaard, Schleiermacher, and another theologian who’d just burst on the scene: Karl Barth. Bonhoeffer would correspond with Barth for the rest of his life.

At university Bonhoeffer discovered a particular passion (initially derived from Holl) for the nature of “duty transformed into joy.”[7] He would go on to write a paper entitled, “Joy in Primitive Christianity” on the “shared joy” (synchairein) in Paul’s writings. Bonhoeffer’s interest in the shared joy of Christian community led to his 1927 doctoral dissertation, a 380-page manuscript called Sanctorum Communio (“The Communion of the Saints”), with the daunting subtitle: “A Theological Study of the Sociology of the Church.” Bonhoeffer claimed that Christ exists as community. Charles Marsh says of Bonhoeffer at this point, “His themes highlighted the uniqueness of his emerging vision and anticipated his life’s work. Christ, community, and conreteness—these were the key words.”

After a short pastorate in Barcelona Bonhoeffer published his Habilitationsschrift (qualifying thesis), entitled “Act and Being: Transcendental Philosophy and Ontology in Systematic Theology.” Upon its successful completion, and meeting a few other academic requirements, Bonhoeffer began to lecture in theology.

So it was at the age of twenty-four, with two dissertations in hand, Bonhoeffer stood on the threshold of a bright academic career in German theological education. He was rooted Kantian philosophy—yet still independent in his formulation, expressing deep affinity for Barth’s burgeoning neo-orthodoxy, concerned with the construction of Christian community, and cherishing rigorous reflection on doctrine. Over the next couple of years two particular experiences would indelibly shape the course of Bonhoeffer’s theological and ministerial trajectory.

The first of which was a sojourn to America. That sojourn we will look at tomorrow.

————————————————————————————————-

[1] Richard Weikart, “Metaxas’ Counterfeit Bonhoeffer,” https://www.csustan.edu/history/metaxass-counterfeit-bonhoeffer

[2] Clifford Gree, “Hijacking Bonhoeffer,” http://www.christiancentury.org/reviews/2010-09/hijacking-bonhoeffer

[3] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Creation and Fall & Temptation (NY: Simon & Schuster, 1997), 10.

[4] Ibid, 30.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Marsh, 4.

[7] Ibid, 44.