The best preachers are physicians of the heart. They have peculiar wisdom in diagnosing the soul’s ailment and prescribing the vital treatment. I long to be like that.

Spiritual Discrimination

The great soul doctors know many spiritual conditions are present in every congregation. They therefore think about different categories of hearers. William Perkins had four categories: 1) the hard heart, 2) the seeker, 3) the converted, and 4) the backslider. Charles Bridges, in his classic The Christian Ministry, was even more detailed. His first category consists of “the infidel,” a hearer impatient with all moral restraint and lives in defiance of God’s rule. Second, there are ignorant and careless listeners. These people simply don’t know or understand the gospel. The self-righteous soul occupies Bridges’ third category. Then comes the “false professor,” one who has been persuaded of the gospel, yet doesn’t embrace it in his life. Such a person, Bridges says, has “no dread of self-deception, no acquaintance with his own sinfulness, no assault from Satan, because there is no real exercise of grace, or incentive to diligence.” To these categories the old Englishmen adds the young Christian, the unestablished Christian, the backslider, and the confirmed and consistent Christian.

If you think Mr. Bridges is specific, then you ought to run down an old Tim Keller article from the Journal of Biblical Counseling titled, “A Model for Preaching (Part 2).” There the Manhattan Man offers a list of “Possible Spiritual Conditions in an Audience.” He has non-Christians, conscious unbelievers, non-church nominal Christians, church nominal Christians, awakened sinners, and apostates. He then categorizes Christians into seven groups: new believers, mature and growing Christians, the afflicted, the tempted, immature believers, the depressed, and the backslidden. And, believe it or not, he has further breakdowns in each category. So “The Afflicted” category includes the physically afflicted, the bereaved, the lonely, the persecuted/abused, the poor, and the deserted.

No wonder Keller seems to wield unusual and pointed force in his heart-searching application.

Do you have a method for wisely discriminating between hearers when you preach? If not, here’s another one that might be of great help.

A Memorable Method

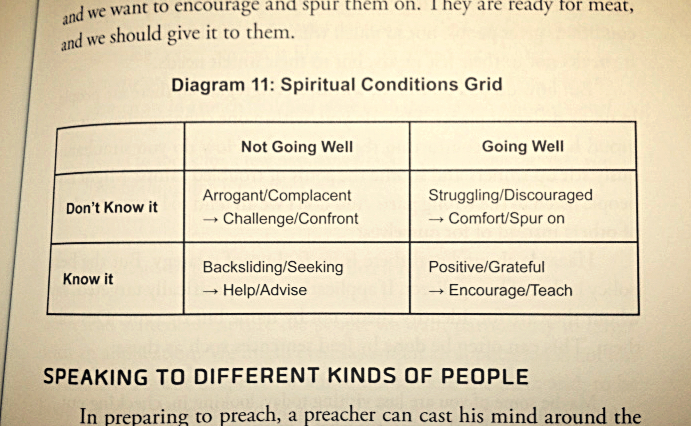

Murray Capill’s excellent book The Heart is the Target: Preaching Practical Application from Every Text offers a wonderful “Spiritual Conditions Grid” for preaching to different kinds of hearers. It’s simultaneously simple and searching.

1) Those who are not going well and don’t know it. Capill says, “This is a dangerous place to be, and can be the condition of both believers and unbelievers.” These people are deceived into believing they are fine, but they don’t realize they are wretched, poor, blind, and naked (cf. Rev. 3:17). They may be smug in their unbelief, complacent in their immature faith, or wayward in their pursuit of God. Either way, they are those the preacher must shake up spiritually and call to repentance.

2) Those who are not going well and know it. Many people – Christian and non-Christian alike – will come to hear a sermon knowing their life is a spiritual train wreck. Maybe they are consciously backsliding into sin and temptation. They might truly believe, but long for God to help stifling, present unbelief. Or it may just be that they are quite young in the faith and need spiritual aid. Some unbelievers will come to the church’s gathered worship knowing they are apart from God, under His wrath, but don’t know what to do about it. Will you help them? Will you provide wise counsel and direction for their soul?

3) Those who are going well and don’t know it. We all have these, don’t we? The tenderhearted souls who constantly feel inadequate. The sensitive conscience who is inclined to undue worry, guilt, and condemnation. Capill writes, “These people need encouragement and consolation. They need the load to be lightened.” Plead with them to come to Christ’s rest and make sure you don’t tie a Pharisaically heavy load on their necks.

4) Those who are going well and know it. These are people who believe the gospel, love the Lord, and warmly respond to God’s Word. They are humble, hopeful, and grateful children of God. They come to feast upon the red meat of Scripture, so we must serve an exquisite meal of encouragement and doctrine for their pilgrim way.

Hit the Target

The heart is the target. Let us, with the Spirit’s help, drive the arrow of God’s truth home into the souls of our people. If the arrow needs to be a flame of fire, then light it up. If it needs to be a calm balm of comfort, let it soar. Know the diversity of conditions ordinarily present in your flock. Do the hard work of putting the text into their respective conditions and you’ll find God’s truth stinging and singing.