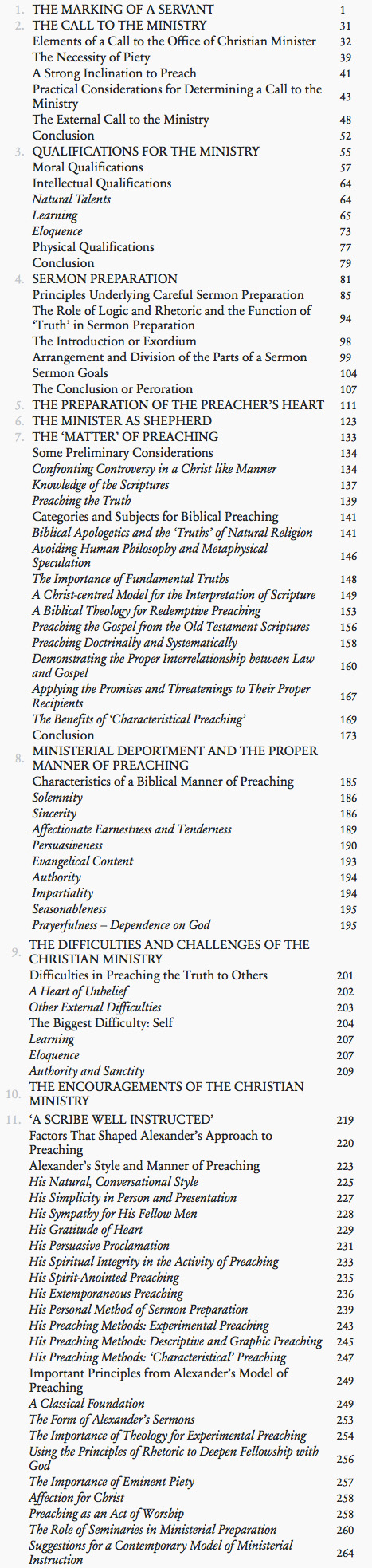

Preaching Christ is the grand work of ministry. As with all great things, it can sometimes be difficult to describe. Nevertheless, there are at least three points worth discussing when thinking about what it means to preach Christ.

Preaching Christ is a hermeneutic.

Read through the apostolic writings, and you’ll discover their hermeneutical key: Jesus Christ. We must learn to read the Bible like Peter and Paul. Pastoral ministry is in a sad state if the apostles wouldn’t recognize the average pastor’s exegesis. Said differently, we’ve got it all wrong if the apostles couldn’t pass the normal hermeneutics course at a seminary. Dennis Johnson has rightly answered the concern of “whether it is legitimate to learn biblical hermeneutics and homiletics from the apostolic exemplars of the New Testament, because their interpretation by the Spirit of God gave them privileged access to revelatory resources not available to ordinary Christians and preachers.”[1]

The answer is, “Yes! The apostles are the master teachers.” The same Spirit working through them works through us to preach the same Christ.

We can—and should—preach Christ from every genre, theme, image, figure, and event in Scripture. Many helpful grids exist on seeing, and thus speaking, Christ from all of Scripture. For example:

- Sinclair Ferguson offers four relations: 1) relate promise and fulfillment, 2) relate type and antitype, 3) relate the covenant and Christ, and 4) relate the proleptic participation in salvation and subsequent realization.

- Sydney Greidanus uses seven ways: 1) the way of redemptive-historical progression, 2) the way of promise and fulfillment, 3) the way of typology, 4) the way of analogy, 5) the way of longitudinal themes, 6) the way of New Testament references, and 7) the way of contrast.

- David Murray teaches ten ways to preach Christ: 1) in creation, 2) in Old Testament characters, 3) in God’s appearances, 4) in God’s law and commands, 5) in Israel’s history, 6) in the prophets, 7) in the types, 8) in the covenants, 9) in the proverbs, and 10) in the Biblical poets.

- Gary Millar lists nine ways to get to Christ: 1) following out a theme through every stage to Jesus, 2) jumping immediately to fulfillment in Christ, 3) exposing a human problem and showing Jesus as the solution, 4) highlighting a divine attribute and showing Jesus as its ultimate embodiment, 5) focusing on the diving saving action in the text and salvation, 6) explaining a theological category and tying it to Christ, 7) pointing out sin’s consequences and finding the only remedy in Christ, 8) describing an aspect of human godliness and goodness and showing Christ as the epitome of it, or 9) seeing a human longing and pointing to Christ as its satisfaction.

Preaching Christ is an instinct.

Reject all formulas for preaching Christ. I’m sure we’ve all heard predictable “Christ-centered” sermons where the Savior pops up at the very end as the solution to a perceived problem in the text. We can, and must, do better.

In an article on “Preaching Christ from The Old Testament Scriptures,” Sinclair Ferguson writes,

Many (perhaps most) outstanding preachers of the Bible (and of Christ in all Scripture) are so instinctively. Ask them what their formula is and you will draw a blank expression. The principles they use have been developed unconsciously, through a combination of native ability, gift and experience as listeners and preachers. Some men might struggle to give a series of lectures on how they go about preaching. Why? Because what they have developed is an instinct; preaching biblically has become their native language. They are able to use the grammar of biblical theology, without reflecting on what part of speech they are using. That is why the best preachers are not necessarily the best instructors in homiletics, although they are, surely, the greatest inspirers of true preaching.[2]

Consider a few ordinary illustrations of this point, beginning with the greatest jazz musicians. They have honed their craft to such a degree that not only is improvisation natural, but such instinctual on-the-spot playing is also their greatest joy. They are experts in scales, patterns, and keys. Therefore, playing their instrument is little more than the overflow of lifelong preparation that has sharpened musical instinct.

Preaching Christ must be the same. We have learned the types and contours of redemptive history to such a degree that we can’t help but pour forth Christ from every sermon.

A second illustration is how reading the Bible is like watching a movie with a startling ending. When you watch the movie the second time, you can’t help but interpret everything in light of your new understanding of the end. Once we realize that all Scripture points to Christ, the Spirit constrains us to preach the Savior from every page. We are not to be like Mary in the garden near Jesus’ tomb. Jesus was in front of her, yet she didn’t notice because she didn’t expect Him to be present. We know the full story: He’s there. So we look for Him in the text.

Preaching Christ is an encounter.

“Him we proclaim,” Paul announces in Colossians 1:28. He doesn’t say, “We explain truths about Christ.” No: we preach Christ.

True preaching is a personal encounter with a personal Savior. The truth is a person (John 14:6). An especially instructive text on this point is Ephesians 2:17: “And he came and preached peace to you who were far off and peace to those who were near.” The “he” is Jesus Christ. We must ask, “When did Christ come and preach to the Ephesians?” Various interpretations exist. But the right view is that Christ came to Ephesus through apostolic preaching. Christ still comes through faithful preaching.

The Second Helvetic Confession knows that preaching God’s word is an encounter with the living Word. Chapter 1 has a section titled, “THE PREACHING OF THE WORD OF GOD IS THE WORD OF GOD.” The first sentence confesses, “Wherefore when this Word of God is now preached in the church by preachers lawfully called, we believe that the very Word of God is proclaimed, and received by the faithful.” The Genevan Confession of 1537 says something similar: “As we receive the true ministers of the Word of God as messengers and ambassadors of God, it is necessary to listen to them as to him himself.”

Encountering Christ through the faithful preaching of his word is not a mere experience of the Savior: it’s a confrontation. Hear Paul’s word on this from 2 Corinthians 2:15–17, “For we are the aroma of Christ to God among those who are being saved and among those who are perishing, to one a fragrance from death to death, to the other a fragrance from life to life. Who is sufficient for these things? For we are not, like so many, peddlers of God’s word, but as men of sincerity, as commissioned by God, in the sight of God we speak in Christ.” There is no such thing as a neutral encounter with Christ. You are for Him, or you are against Him. You are in the light or the dark. You are receiving Him or rejecting Him. There is no neutral ground with Christ. Mere sympathy towards Christ has never saved a person. Detachment from Christ has never delivered anyone from sin and Satan.

Stick around for “Part 2,” which thinks about four other points on preaching Christ.

[1] Johnson, Him We Proclaim, 2.

[2] Ferguson, Some Pastors and Teachers, 672.