Thomas Murphy (1823–1900) was an Irish-American Presbyterian who pastored Frankford Presbyterian Church from 1848–1885. He trained for the ministry under the brilliant men at Princeton Theological Seminary. The professor that left an indelible mark on Murphy was Archibald Alexander. Murphy especially loved Alexander’s lectures on Pastoral Theology. Murphy took “copious notes” of almost everything he heard Alexander say about “the character, duties and responsibilities of the pastoral office.” Eventually, Murphy turned them into an excellent, yet all-too-neglected 1877 book Pastoral Theology: The Pastor in the Various Duties of His Office.

If you’re in ministry and haven’t read it, I’d encourage you to work through Murphy’s manual. You don’t even have to spend a penny for his thoughts!

A Significant Silence Today

Maybe I’m cynical. Or maybe I’m not listening to the right voices. But I keep asking, “Who today calls for pastoral holiness with the earnestness of Christ and his apostles?” You need only turn to John 15:4–5, 1 Timothy 4:7–16, and 2 Timothy 2:20–21 to see how holiness is the central concern for Christ’s ambassadors.

I assume one reason is that we’ve overemphasized contextualization, entrepreneurial skills, and worldly rhetoric in recent decades. Wondering if God’s word is sufficient God’s word, we’ve baptized cultural practices and imported them into the ministry.

You can also pay attention to the popular platforms of the most popular ministers. Each one has “their thing”: healthy churches, radical missions, confessional theology, and racial reconciliation. These are all good and necessary. But who is the person that is relentlessly and winsomely calling gospel ministers back to the things of first importance: knowing the love of Christ and returning love to Christ?

Perhaps we can’t name such a person because there’s little interest in the priority of piety. Could it be that we’ve cultivated churches that are skeptical about passionate pleas for Christ-centered, Spirit-powered godliness? Perhaps many church members—and church leaders—are more excited about becoming a huge, growing congregation than about hearing Christ from a holy, maturing minister. Yet it’s the latter reality that God has decreed an ordinary means of saving sinners and sanctifying saints (see Rom. 10:17; 1 Tim. 4:15–16).

Let us together begin to trod on the ancient paths.

It Used to Matter

YHWH spoke in Jeremiah 6:16, “Thus says the Lord: ‘Stand by the roads, and look, and ask for the ancient paths, where the good way is; and walk in it, and find rest for your souls.’” Give us, I say, the ancient directions that lead to life. Show us, I plead, the old paths that point us to Christ.

Thomas Murphy knows the way. And we should listen carefully.

Chapter two of his Pastoral Theology is titled, “The Pastor in the Closet: The Piety Which is Needful for the Pastoral Office.” His opening salvo about spirituality is tremendous—and needed. Here’s what he says:

It should be laid down as our first principle that eminent piety is the indispensable qualification for the ministry of the gospel. By this is not meant simply a piety the genuineness of which is unquestionable, but a piety the degree of which is above that of ordinary believers. It is meant that there should be a more thorough baptism of the Holy Ghost, a more absolute consecration of all the powers and faculties to the service of God, a more complete conformity to the likeness of the Lord Jesus, a greater familiarity with the mind of the Spirit, a nearer approach to the perfect man in Christ Jesus, in those who take upon them the privileges and the responsibilities of the pastor, than are commonly expected even in true Christians. The pastor should not be satisfied with reaching the general standard of spirituality. He has devoted himself to a high and holy office to which he believes himself called, and hence he has need of a very high tone of piety. As a minister appointed to serve in the sanctuary and wait upon souls, how deep should be his humility. His great aim is to save men, and it will not therefore suffice for him to have merely the ordinary sympathy with the suffering and the lost. He is to be a leader in the spiritual host of God; must he not go before others in spiritual attainments?

Do you think he’s too earnest? Does he demand too much? I think he’s got it quite right.

James’ heart burns for passion in the pulpit. He’s on point with what’s necessary for heralding Christ. He knows that it’s not until the preacher’s heart is right that his sermon will cut straight. Listen to what he says is “the essential qualification” for earnestness in the ministry:

James’ heart burns for passion in the pulpit. He’s on point with what’s necessary for heralding Christ. He knows that it’s not until the preacher’s heart is right that his sermon will cut straight. Listen to what he says is “the essential qualification” for earnestness in the ministry:

A Legacy of Preaching, Volume Two–Enlightenment to the Present Day explores the history and development of preaching through a biographical and theological examination of its most important preachers. Instead of teaching the history of preaching from the perspective of movements and eras, each contributor tells the story of a particular preacher in history, allowing these preachers from the past to come alive and instruct us through their lives, theologies, and methods of preaching.

A Legacy of Preaching, Volume Two–Enlightenment to the Present Day explores the history and development of preaching through a biographical and theological examination of its most important preachers. Instead of teaching the history of preaching from the perspective of movements and eras, each contributor tells the story of a particular preacher in history, allowing these preachers from the past to come alive and instruct us through their lives, theologies, and methods of preaching.

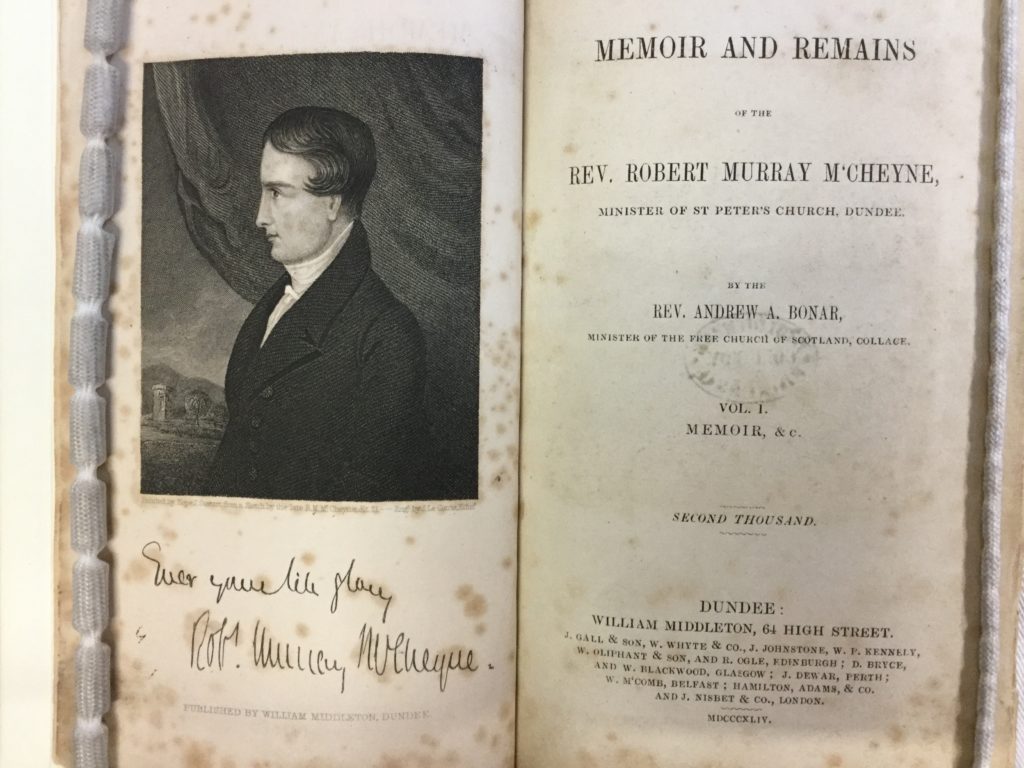

One of the more fascinating observations in my studies on M’Cheyne was Andrew Bonar’s experience in writing the Memoir. Here’s what we find in Bonar’s

One of the more fascinating observations in my studies on M’Cheyne was Andrew Bonar’s experience in writing the Memoir. Here’s what we find in Bonar’s  Here’s how Crossway describes the book:

Here’s how Crossway describes the book:

After hearing the great Dr. Fairbairn preach, Jowett told his students at Airedale College, “Gentlemen, I will tell you what I have observed this morning: behind that sermon there was a man.” Although The Preacher provides scant autobiographical information, I always have same sense in reading Jowett’s work—there is gravity in his message.

After hearing the great Dr. Fairbairn preach, Jowett told his students at Airedale College, “Gentlemen, I will tell you what I have observed this morning: behind that sermon there was a man.” Although The Preacher provides scant autobiographical information, I always have same sense in reading Jowett’s work—there is gravity in his message.

Seeking a Better Country: 300 Years of American Presbyterianism

Seeking a Better Country: 300 Years of American Presbyterianism  A Brief History of the Presbyterians

A Brief History of the Presbyterians  Reformed Theology in America: A History of Its Modern Development

Reformed Theology in America: A History of Its Modern Development  Presbyterians and American Culture by Bradley Longfield

Presbyterians and American Culture by Bradley Longfield