If we are ever to see a revival in our nation, it will begin with a revival of real gospel ministry. Pastoral paradigms built on pragmatism must fall, and in their place, we will see a renewed passion for prayer and piety. The kind of preaching that the Spirit blesses (and the heraldic ministry that ushers in revival) is that which is saturated in prayer and comes from the mouth of a man consumed with holy love for Christ. Before he ever considers strategic vision, administrative planning, and staffing structure, God’s man must be a man of God—in doctrine and devotion.

Should God grant me many years in ministry, I want to see this kind of renewal visit our ministers. But such a renewal comes with a perennial peril.

Learning a Vital Lesson

As I’ve studied Robert Murray M’Cheyne over the last few years, one of the more noticeable lessons his life teaches is the full-orbed nature of pastoral piety. We need to understand this totality of holiness in two ways. First, for M’Cheyne, piety begins with love for Christ. It then flowers into every area of spirituality: devotion to prayer, God’s Word, the Lord’s Day, evangelism, friendship in the church, dependence on the Spirit, and “unfeigned humility.” Secondly, we must see that an earnest pursuit of piety is a dangerous one. We can make much of godliness—it’s necessity and nature—that people overestimate our actual holiness. It’s one thing to be a holy man, but it’s entirely different to be known, even famed, for holiness.

M’Cheyne was such a minister.

The Snare Exposed

M’Cheyne once wrote, “I earnestly long for more grace and personal holiness, and more usefulness.” Nothing communicates M’Cheyne’s longing more than his Reformation.

Written in late 1842 or early 1843, it is his ten-page resolution for personal holiness. In the first section, he concentrated on “Personal Reformation,” saying,

I am persuaded that I shall obtain the highest amount of present happiness, I shall do most for God’s glory and the good of man, and I shall have the fullest reward in eternity, by maintaining a conscience always washed in Christ’s blood, by being filled with the Holy Spirit at all times, and by attaining the most entire likeness to Christ in mind, will, and heart, that it is possible for a redeemed sinner to attain to in this world.

M’Cheyne proceeded to delineate a scheme for personal holiness that would enable him to live in increasing communion with Christ. The plan included strategies for confessing sin, reading Scripture, applying Christ to the conscience, being filled with the Spirit, growing in humility, fleeing temptation, meditating on heaven, as well as studying specific Christological subjects.

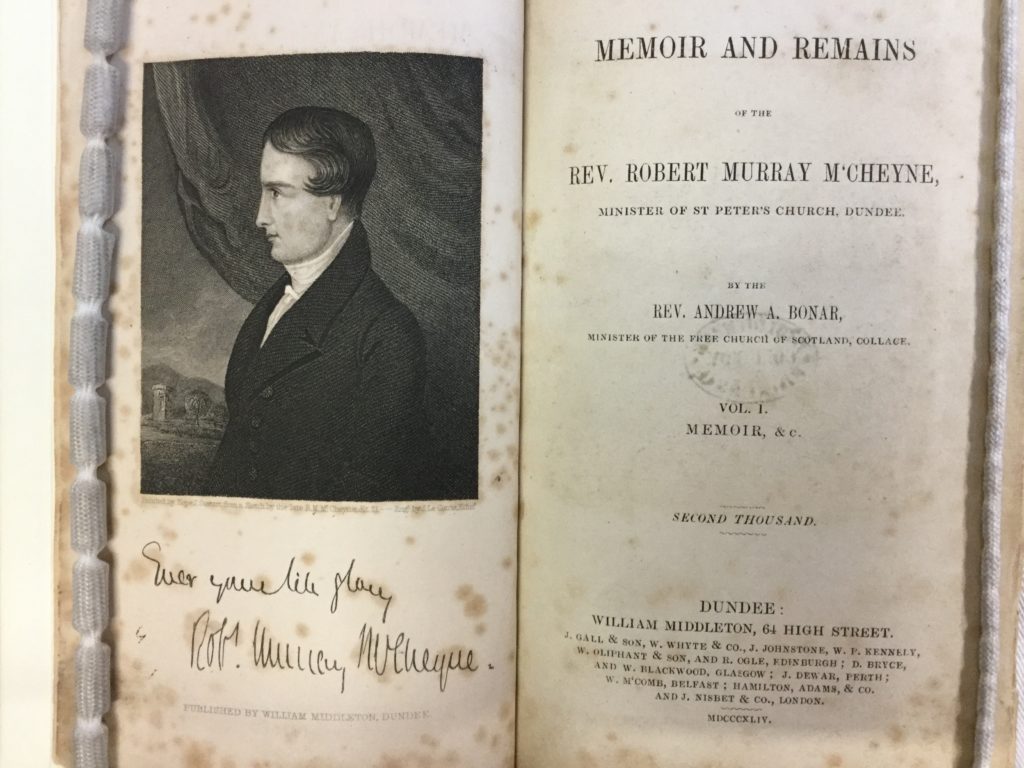

His devotion to Christ was so renown that almost every epigram after his death referred to him as “the saintly ministry” or “the godly pastor” of St. Peter’s. His friend and biographer, Andrew Bonar, made an astute observation on a common pitfall in pastoral piety:

An experienced servant of God has said, that, while popularity is a snare that few are not caught by, a more subtle and dangerous snare is to be famed for holiness. The fame of being a godly man is a great a snare as the fame of being learned or eloquent. It is possible to attend with scrupulous anxiety even to secret habits of devotion, in order to get a name for holiness. If any were exposed to this snare in his day, Mr. M’Cheyne was the person. Yet nothing was more certain than that, to the very last, he was ever discovering, and successfully resisting, the deceitful tendencies of his own heart, and a tempting devil. Two things he seems never to have ceased from—the cultivation of personal holiness, and the most anxious efforts to save souls.

Examine Yourself

Ever since I first read it, these two sentences in the quote above have been a constant warning: “The fame of being a godly man is a great a snare as the fame of being learned or eloquent. It is possible to attend with scrupulous anxiety even to secret habits of devotion, in order to get a name for holiness.”

I’m not known as a holy man. But I recognize how easy it is to devote oneself to the means of grace and forget that your real motivation is selfish to the core: “I make much of such devotion so people will make much of my devotion.” Thus, the pastor’s pursuit is only in service of self, not the Savior. The Spirit won’t revive His church with such a man.

Pastors then must be wary of their motives in pursuing piety. They must resist the praise of men, and live only for the smiles of God. They must recognize how the devil schemes, even in our noble endeavors, and live for Christ’s honor alone.

True holiness is noticeable. Vital godliness leaves a mark. Paul’s teaching to Timothy demands it: “Practice these things, immerse yourself in them, so that all may see your progress. Keep a close watch on yourself and on the teaching. Persist in this, for by so doing you will save both yourself and your hearers” (1 Tim. 4:15–16).

So, yes, let’s pursue personal holiness with extraordinary vigor. But test your motives. Make sure they aren’t, at the root, just a scheme “to get a name for holiness.”

A Legacy of Preaching, Volume Two–Enlightenment to the Present Day explores the history and development of preaching through a biographical and theological examination of its most important preachers. Instead of teaching the history of preaching from the perspective of movements and eras, each contributor tells the story of a particular preacher in history, allowing these preachers from the past to come alive and instruct us through their lives, theologies, and methods of preaching.

A Legacy of Preaching, Volume Two–Enlightenment to the Present Day explores the history and development of preaching through a biographical and theological examination of its most important preachers. Instead of teaching the history of preaching from the perspective of movements and eras, each contributor tells the story of a particular preacher in history, allowing these preachers from the past to come alive and instruct us through their lives, theologies, and methods of preaching.

One of the more fascinating observations in my studies on M’Cheyne was Andrew Bonar’s experience in writing the Memoir. Here’s what we find in Bonar’s

One of the more fascinating observations in my studies on M’Cheyne was Andrew Bonar’s experience in writing the Memoir. Here’s what we find in Bonar’s