Reading church history always humbles the heart. You hear about the mighty ministers of old and the fantastic awakenings that rocked congregations and countries.

I’ve often thought, “What made the old ministers different? Why did they seem to possess such power in the Spirit?”

One Possible Answer

My typical answer to such questions has been to quote something from William Williams of Wern, a former giant of the Welsh pulpit:

The old ministers were not much better preachers than we are, and in many respects they were inferior, but there was an unction about their ministry, and success attended upon it now but seldom witnessed. And what was the cause of the difference? They prayed more than we do. If we would prevail and have power with men, we must first prevail and have power with God. It was on his knees that Jacob became a prince, and if we would become princes we must be oftener and more importunate upon our knees.

Williams said this in the early 1800s. I imagine many of us today think the nineteenth-century giants prayed more fervently than we do. Yet, Williams felt his offering little more than a tiny sparkle compared to a previous generation’s shining commitment to closet prayer. Are we any better today?

It’s typical for every generation to think the preceding one was more potent because they were more prayerful. Listen to what E. M. Bounds wrote in 1907,

The pulpit of this day is weak in praying. The pride of learning is against the dependent humility of prayer. Prayer is with the pulpit too often only official — a performance for the routine of service. Prayer is not to the modern pulpit the mighty force it was in Paul’s life or Paul’s ministry. Every preacher who does not make prayer a mighty factor in his own life and ministry is weak as a factor in God’s work and is powerless to project God’s cause in this world.

We should always consider the possibility that power in prayer is the missing component in many of our ministries.

Or Maybe This is The Answer

Another possible answer, and one I’ve routinely given, relates to personal holiness. In 2 Corinthians 5:14, Paul says the animating center of his ministry is “the love of Christ.” Such love is all-controlling and constraining. A ministry lacking in love for Christ is a ministry shriveled in its strength.

Maybe we’re not as powerful because we don’t love the Savior as we ought.

Someone said of Robert Murray M’Cheyne that “love to Christ was the great secret of all his devotion and consistency.” The analysis was insightful. Read through the various memorials of M’Cheyne’s ministry and you’ll observe a thread: his sincere holiness was singularly attractive. It was often his manner, more than his message, that cut hearts to the quick.

M’Cheyne believed that “it is not great talents God blesses so much as great likeness to Jesus. A holy minister is an awful weapon in the hand of God.”

God delights in using holy vessels in ministry (2 Tim. 2:21). Therefore, we should also reckon with the fact that our small pursuit of holiness prevents greater usefulness for Christ.

Another Answer I Also See

I recently was rereading some of Octavius Winslow’s lovely book, The Precious Things of God. He published the book in a decade of life that saw him bury one of his sons, two of his daughters, his mother, and his wife. I remembered that and thought, “Oh, there’s something there. Perhaps that’s more of the answer than I’ve thought.”

What came to mind was suffering. So many of the mighty giants of old suffered more than we do. They had an increased experience of what God told the apostle Paul, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor. 12:9).

In the Lord’s upside-down kingdom, weakness is the way of power. Undoubtedly, many of them knew this at a level we don’t today.

I rejoice to live in a day when death’s threat is less constant and physical frailties are dealt with swiftly. That doesn’t mean, however, that the weakness that is so often a fruit of suffering cannot grow in the minister’s heart. It should. And it must.

We may struggle with prayer and piety compared to previous generations. And maybe, too, we haven’t learned the holiness and mightiness found in weakness.

A Legacy of Preaching, Volume Two–Enlightenment to the Present Day explores the history and development of preaching through a biographical and theological examination of its most important preachers. Instead of teaching the history of preaching from the perspective of movements and eras, each contributor tells the story of a particular preacher in history, allowing these preachers from the past to come alive and instruct us through their lives, theologies, and methods of preaching.

A Legacy of Preaching, Volume Two–Enlightenment to the Present Day explores the history and development of preaching through a biographical and theological examination of its most important preachers. Instead of teaching the history of preaching from the perspective of movements and eras, each contributor tells the story of a particular preacher in history, allowing these preachers from the past to come alive and instruct us through their lives, theologies, and methods of preaching.

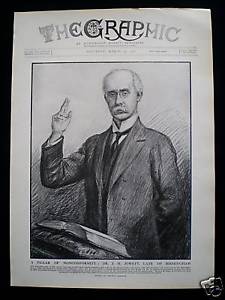

After hearing the great Dr. Fairbairn preach, Jowett told his students at Airedale College, “Gentlemen, I will tell you what I have observed this morning: behind that sermon there was a man.” Although The Preacher provides scant autobiographical information, I always have same sense in reading Jowett’s work—there is gravity in his message.

After hearing the great Dr. Fairbairn preach, Jowett told his students at Airedale College, “Gentlemen, I will tell you what I have observed this morning: behind that sermon there was a man.” Although The Preacher provides scant autobiographical information, I always have same sense in reading Jowett’s work—there is gravity in his message.